If Projects Are Unique, Shouldn’t How We Manage Them Also Be Unique?

BACKGROUND

The question I posed in the title appeared on my radar screen over 30 years ago. I began investigating it and have subsequently written and spoken about it at every opportunity. Even given what we know today it is not uncommon practice for an organization to have a “one size fits all” approach to project management. Such organizations establish a single project management methodology to which all project managers must comply. Compliance often forces project managers to use processes unfriendly to many project situations they encounter. They try to force fit their project into the specified templates and seldom succeed. For a variety of reasons the “one size fits all” approach has never been successful. With project failure rates hovering around 70% maybe we are missing something in the way we approach project management.

The question I posed in the title appeared on my radar screen over 30 years ago. I began investigating it and have subsequently written and spoken about it at every opportunity. Even given what we know today it is not uncommon practice for an organization to have a “one size fits all” approach to project management. Such organizations establish a single project management methodology to which all project managers must comply. Compliance often forces project managers to use processes unfriendly to many project situations they encounter. They try to force fit their project into the specified templates and seldom succeed. For a variety of reasons the “one size fits all” approach has never been successful. With project failure rates hovering around 70% maybe we are missing something in the way we approach project management.

THE PROJECT LANDSCAPE

I am a first generation Polish-American. I have always been a problem solver with a good work ethic. I strive for simplicity, intuitiveness and practicality. So after considerable research and practice I offer the following.

Every project is defined by a goal and a solution to achieve that goal. That seemed like a good starting point and a stable model on which I could base any project management approach I might offer.

There are several ways to define a metric to characterize goal and solution. I considered several and rejected all but one. The simplest and totally intuitive characterization of a project is to use a two-valued metric whose values are:

- clearly defined

- not clearly defined

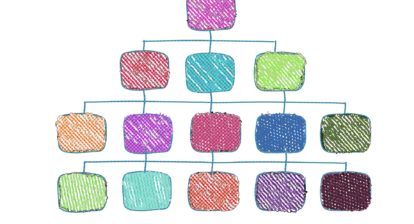

Applying this metric to both the project Goal and the Solution to achieve that Goal produces Figure 1.

Figure 1: The project landscape

Upper-Left: Emertxe Project Management (MPx) Quadrant, Upper-Right: Extreme Project Management (xPM) Quadrant, Lower-Left: Traditional Project Management (TPM) Quadrant, Lower-Right: Agile Project Management (APM) Quadrant.

So there are 4 quadrants that can be used to classify any project that ever existed or will exist. How could it be any simpler? This project landscape has been the bedrock of all tools, templates and project management processes I have shared with the PM Community for the past 20 years.

The projects that are found in each of these quadrants are profoundly different from one another and so are the approaches to effectively managing them. The book from which this article is based guides you through the application of this project landscape to effectively managing projects. For now I want you to know that most of the tools, templates and processes you already know and probably use can be adapted to every project in this project landscape.

Traditional Project Management (TPM) Quadrant

The TPM Quadrant will be most familiar to you for in this quadrant are found the historical roots of project management methodologies. The most common projects are construction projects (buildings, highways, bridges and machinery, for example), some product development projects and a few business process design and improvement projects. These projects are managed using plan driven approaches which are characteristically change intolerant. A variety of waterfall and other linear models are found in the TPM Quadrant.

Agile Project Management (APM) Quadrant

This quadrant and the remaining two quadrants embody what are called complex projects. Complex projects are different than TPM projects because they must be managed in an imperfect world. In a TPM project all goal and solution information is clearly defined and a complete plan including resource requirements and work schedules can be developed before the project work begins. This is not the case for complex projects. Rather than being change intolerant as the TPM models are, the complex project management models thrive on change-based approaches as the only way to discover acceptable solutions. APM models are iterative models designed to learn and discover complete solutions.The approaches we will develop all utilize just-in-time planning models as the most cost effective solution discovery processes. Scrum is a popular complex project management model often used for software development projects.

The first and most frequently encountered complex situation are those projects where the goal is clearly defined but how to achieve the goal is not. These are APM projects. The lack of solution clarity may be the absence of a minor feature or function to almost a complete lack of knowledge of any solution. The portfolio of agile processes span all of the projects in the APM Quadrant and will be a major focus in your journey.

Here are two examples of the range of APM projects. The first example involves product distribution. Given a master list of delivery locations and the product orders from each location how many trucks are required to minimize total delivery costs while satisfying order demand. This is a routing problem with a variable number of routes but fixed delivery locations. Some variant of a heuristic algorithm is needed. At the other extreme where very little of the solution is known consider the challenge put forward by President John F. Kennedy in 1961 to put a man on the moon and return him safely by the end of the decade. I worked on that project and was part of the team that was trying to find a propulsion solution using a nuclear reactor as the power source. I remember sitting in the meeting where the engineers on our team didn’t have much of an idea of what the solution (if there was one) would look like. It would be at least 30 years before there would be a project management process appropriate for this project.

Extreme Project Management (xPM) Quadrant

This situation is common in new product development, business process design and R&D projects. The goal might be a statement of a future state that would be nice to reach but the way to realize that future state is not known and may never be known. As the search for that solution commences constraints are discovered and the future state is revised. So both the goal and the solution changes through iteration. Hopefully the project converges to a single solution to some goal. The final decision is to assess the acceptability and business value of the goal. Clearly these are high risk projects.

Emertxe Project Management (MPx) Quadrant

This looks like a nonsense category – solutions out looking for problems. You can probably name a few consulting companies that actually take this approach. Right! But, in fact, MPx projects occur quite commonly in research and development, especially in the discovery and manufacture of new drugs. Here’s a hypothetical but realistic example. A primitive tribe in a remote village in the Andes mountains have an average life span of 90 years. Extensive research has identified that their diet is heavily dependent on the roots and sap from a tree that grows only in their location and that they claim is the cause of their longevity. So the question is what, if any, medicinal value does the tree offer. And so we have a solution (the tree) but what is it a solution too (the goal).

For a real life example, consider Radio Frequency Identification (RFID) technology. It is a solution but for what business applications (the goal)? Early in the life of RFID Wal-Mart was interested in using RFID for warehousing and physical distribution applications. After extensive evaluations Wal-Mart concluded that the then current RFID was not accurate enough to produce any meaningful business value. Costs exceeded benefits. That report by Wal-Mart may be credited with RFID technology advances that eventually produced meaningful business value and led to the many applications we enjoy today.

And for yet another application consider application software evaluation projects. The solution is clearly defined by an existing software package, say an HRMS system. Can the solution be implemented in your company to meet your HR management requirements. This can be a major project if it requires revision to existing business rules or presents interface obstacles to existing software applications.

IN CONCLUSION

So where do you go from here?

First, you need to understand the complexity of the Project Landscape. I have defined four categories of projects that are profoundly different from one another and whose effective management processes will also be profoundly different. While this may seem like it is an overwhelming management challenge, it isn’t. A portfolio of tools, templates and processes, many that you already use, is all you will need. What you don’t have is the discipline of thinking like a project manager so that you can adapt this portfolio to a variety of project challenges.

This article is excerpted from “Effective Project Management: Traditional, Agile, Extreme, 6th Edition” (EPM6e) by Robert K. Wysocki.