Trust Building between Stakeholders and the Project Team Is a Powerful Asset

The following statement made by Dr. Gary L. Richardson, University of Houston, is one of the most commanding I ever heard related to project management and one that all project managers (PMs) should be aware of: “Projects are natural breeding grounds for conflict resulting in ineffective human behavior, which must be dealt with effectively for the overall success and health of a project.”

Every organization has unique power struggles due to changing constraints to project resources, environments, goals, and/or deliverables. Competition for resources makes conflict a dominant issue, and PMs must pay attention to company politics to be effective. Usually, the most difficult limitation for a PM is getting the right team “loaned” to them from different functional or line managers (e.g., database, security, and/or infrastructure). Keep in mind that the selected members owe their first loyalty to their functional manager, and that they might be assigned to multiple projects, which eventually might cause problems in meeting individual project milestones. Furthermore, outsourcing can come into play, often motivated by a desire to cut costs, but causing potential gaps in operating performance.

I have seen many PMs assigned a full time project that runs close to a year or beyond that should have their own office and/or team work room to be more productive. More often than not, though, this isn’t allowed them, and the lack of required work space results in difficulty. Remember, organizations need to be supportive to their PMs in order to have successful projects.

Trust building between stakeholders (those with a vested interest in the outcome of a project) and a project’s team fosters loyalty and results in a positive working environment that increases the chances of success. In most companies there’s room for improvement—wouldn’t you agree?

Two areas, in particular, are important to look at: a project’s charter and the communications plan. We’ll cover both below.

The Project Charter

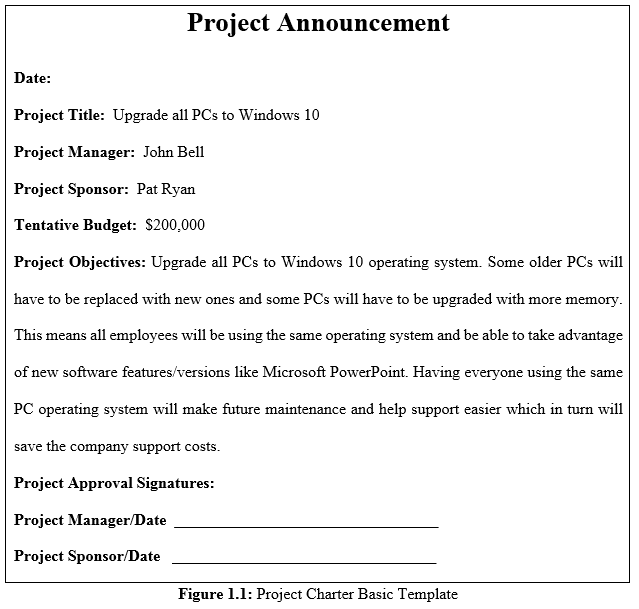

A new project requires planning, skilled leadership, and a little luck. Since every organization is unique, the approach or model for a formal Charter varies, but always should build a business case outlining the value of the project and procuring sign off by management. The Charter serves as a high-vision target that is used to produce a business case and hopefully leads management to further approve a more detailed definition (e.g., scope document). In other words, a Charter is like a formal press release (usually 1 – 3 pages) to the organization that a specific project is being authorized for further study of its value. At the end of the charter process, management will either decide to reject, put-on-hold, approve with modifications, or approve the development and implementation of the project.

At a bare minimum, a Charter (see Figure 1.1) will include the name of the PM, project sponsor, tentative budget, and the project objectives. A project sponsor is a person who normally has a large degree of influence in the organization, typically is responsible for the budget, usually reaps the benefits of the project, and champions the project through its approval phases.

Some organizations go way beyond the basic template shown in Figure 1.1 and might produce a longer charter that goes into the number of team resources needed, their names, key deliverables, realistic cost estimates, risk summary, success criteria, and what the of PM’s authority is. More detail is always better in making a “go or no go” decision, but it takes more time to do this. A long charter could end up being the foundation for a scope statement, which defines a project’s boundaries such as what is included (e.g., deliverables) and what is not included (e.g., elimination of mistakes and sometimes dangerous assumptions).

A Communication Plan

Project status tracking and reporting processes should be defined at the start of any project as part of the communications plan, which describes the information needs of the stakeholders, project sponsor, and the project team. This overall communications plan should cover who needs to know what, when they need to know it (e.g., weekly, bi-monthly, or monthly), and how the information should be received (e.g., paper, email, or a collaboration website). It’s important that the PM ask each stakeholder to pinpoint their preferred form and frequency of desired communication. Their needs usually depends on how active the stakeholder is in the project (e.g., an occasional contributor or someone that is providing financial/political support). There are many ways of reporting a weekly, bi-monthly, or monthly status of a project. As much as possible, Microsoft’s Project, Excel, Visio, and/or PowerPoint graphics should be used to depict the status of a project which is easier for non-technical people to visualize and understand.

Depending on the size and length of a project, PMs need to have status meetings at least two to four times a month with their stakeholders to cover the progress made and mitigate risks before they become issues which could hinder the development of team relationships. Meeting less frequently allows problems to fester unchecked and could thereby do great harm to the overall project (Whitten 1995).

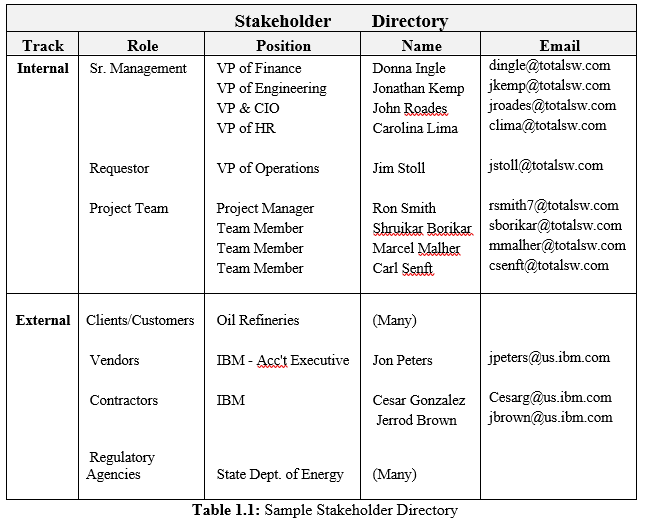

The Useful Stakeholder Directory

It’s also smart in the beginning of a new project for the PM to generate a Stakeholder Directory (see Table 1.1), which allows you to make sure you identify the right people to focus on. This is a living document that will like be in need of constant updating. If in doubt about a stakeholder, include the person, and if you find out later they aren’t interested, delete the name. It’s better to be safe than sorry. The table template below could be expanded to put in other useful fields. For example, you need to know if the stakeholder is a driver, supporter, or an observer. A driver is someone that defines the results, a supporter is someone that helps you, and an observer is someone that is interested in your activities and results.

Keep in mind there might be some stakeholders who view the project negatively (e.g., a new system might reduce their head count or they have a personal agenda that is not being addressed for the good of the whole). Pay attention to these issues, left unaddressed could hurt the project’s outcome. If there are a lot of politics at play, it’s important that the PM and the sponsor recognize this and do their very best to work along with dissenting people. In Part Two of this article, I’ll be bringing some suggestions for building trust between stakeholders and project team members.

Eric Uyttewaal

Ronald, great post, once again! I find myself looking forward to your next writing. One small side observation: I recommend you add a column to the stakeholder directory in which you try to describe what stake each stakeholder has and if that stakeholder is expected to work on behalf of the project or against it and why. Just my two cents today … Eric

Jigs Gaton

Great stuff Ronald, as always 🙂