Author: Ronald B. Smith, MBA, PMP

Ronald Smith has over four decades of experience as Senior PM/Program Manager. He retired from IBM having written four books and over four dozen articles (for example, PMI’s PM Network magazine and MPUG) on project management, and the systems development life cycle (SDLC). He’s been a member of PMI since 1998 and evaluates articles submitted to PMI’s Knowledge Shelf Library for potential publication. From 2011 - 2017, Ronald had been an Adjunct Professor for a Master of Science in Technology and taught PM courses at the University of Houston’s College of Technology. Teaching from his own book, Project Management Tools and Techniques – A Practical Guide, Ronald offers a perspective on project management that reflects his many years of experience. Lastly in the Houston area, he has started up two Toastmasters clubs and does voluntary work at various food banks.

Integrated Change Control

Very few projects run exactly to plan. This happens for a number of reasons (one example is scope creep). The bottom line is that you should expect changes to happen! Integrated change control (ICC) is the process of reviewing all change requests, approving changes, and managing changes to deliverables with documentation. It also involves communicating decisions that have been made. ICC consists of many overlapping areas, such as change management, project management, configuration management (CM), and the change control board (CCB). See Figure 1.1 below. Let’s look at each area: Change Management: Within information technology (IT) systems and quality managing systems (QMS) is a strategy and process used to insure that changes to a product or service are introduced in a controlled and contained way. This ensures that any negative effects of a change are minimized. The core of ICC is establishing the CCB, thus documenting the extent of its’ authority. Therefore, change management will impact the decisions made by the CCB and is a key factor to reducing failures and having successful project management. Project Management occurs when project managers (PMs) strive to meet the specific scope, time, cost, and quality goals of their baselined projects. In doing so, they use knowledge, skills, tools, and techniques to meet their project requirements. The PM notifies everyone affected by their approved CCB changes in a timely manner. Configuration Management (CM) involves identifying and controlling the functional and physical design compositions of the product or service. Common document control software used by CM is Information Technology Infrastructure Library (ITIL), which contains a set of practices on aligning its’ services with the needs of the business. It boils down to figuring what you have, controlling who can make changes, and keeping a record of the changes made. Change Control Board (CCB): The CCB consists of a formal group of people (i.e., key stakeholders and subject matter experts/PMs, as needed) who are responsible for reviewing, approving, rejecting, and/or deferring changes within a project. The key functions of a CCB (see Figure 1.2) are to provide guidelines for preparing project change requests (PCRs or CRs), assessment/analyzing CRs, and managing the implementation of approved changes. Typically in large organizations, CCB meetings are scheduled on a weekly basis (these meetings may be done by conference call). It is the responsibility of the change manager to send out the CRs for discussion prior to the meetings. Each participant has the chance to review proposed changes and gather any relevant information before the scheduled meeting. During a typical CCB meeting, the change proposals are reviewed and a “go” or “no go” decision is made for each proposal. The approved CRs are then prioritized for scheduling purposes because there is usually a limit on available resources and money. Keep in mind that maintaining quality is an important part of this decision making process. Here are some guidelines to follow when conducting CCB meetings: When you have a large number of small changes, it may be more efficient to bundle them together into one CR package, so that everyone’s time is managed more effectively. Keep in mind, some changes can likely be made at zero or near zero cost. Trigger automatic approval for CRs that have little or no effect on schedule, cost, or scope with a set threshold (for example, those at a $500 or below cost). Have a special process in place to handle emergency CRs (for example, a backup disaster recovery system that stopped working). These are items that need to be addressed immediately. With a process for handling such issues, changes can be put into place before the next scheduled CCB meeting. Check to see if there are any relationships between the submitted CRs and ones already being worked on. A lot of different outcomes may happen depending on the scenario, and you want to avoid duplication. For example, combining CRs, rescheduling the work, stopping work on an approved CR, or not approving a submitted CR because of its’ being a duplicate. It’s important to discuss the risk/rewards of each CR. Analyze the impact both to the project and to the organization. Don’t be hesitant about saying “No” to CRs in order to promote a steadier work environment and ensure that only critical CRs are implemented. Furthermore, if a CR is incomplete or not worth the time to analyze, it should be rejected immediately. Change process documentation (for example, CR Submission Forms or CR Tracking Documents) is important because it helps to manage the flow of requests through the process. These forms can be easily generated in Microsoft Word or Excel. In the long run you would be better off using Excel because it would be easier to track changes and display selected data using the Sort and/or Filter features. Compile a list of lessons learned after completion and final acceptance of the change. This includes input from the person initiating the CR and the affected customers. This information could be invaluable for future projects. Configuration Management in Integrated Change Control A big part of the documentation control process is CM where the flow of product and project documents are controlled in the CM libraries filed by documentation type with version control references. The ICC process utilizes CM for the supporting documentation (for example, functional and physical characteristics of the project’s products) as it moves through the decision process. ITIL is a broad set of references that explain effective ways to handle many aspects of IT support and delivery, including asset and configuration management, change management, release management, and problem management. Also the CM repository can be used for Incident Management (IM). An incident is an unplanned event that could lead to a loss or a disruption of running a business. A few examples: Cybersecurity threats Supply chain disruption Brand reputation attacks on social medium Product quality issues Workplace violence Terrorist activities Data breach Natural disasters Software tools such as ServiceNow and BMC Remedy have been widely adopted and integrated with other systems (especially ITIL) to manage problem resolution. BMC Remedy automates standard ITIL processes out of the box. Extensive configuration options enable you to tailor chosen applications to the needs of your organization. This is based on a response plan that defines what constitutes an incident and delivers step-by step procedures for each defined incident. If you want more information on this topic, visit the Institute of Configuration Management website (www.icmhq.com). Summary Successful change management depends on identifying, evaluating, and managing change events in a project and eventually in the end user environment. The ICC process or components are controlled by the CCB or steering committee, and thus supported by a formal workflow process and appropriate communication technology. The key functions of CCB are to provide guidelines for preparing CRs, evaluating them, and managing the implementation of the approved changes. Another good idea is for the PM to create custom field(s) in Microsoft Project to flag change request tasks, which later can be filtered to only view the tasks with the change request tag. For example, the custom flag field could have the CR number or date of the approved CR. Better still, you could have two custom flag fields – one for CR number and one for date approved. PMs should be involved in managing the project changes by delegating the work and/or being part of the team making the changes. Keep in mind, CRs will more than likely change the original critical path (Note: Microsoft Project will show the critical path using the Filter feature), resulting in a new estimated completion date for the project. Another key factor in change control is for the PM to use written and oral reports to notify everyone affected by a change in a timely manner. Some major approved changes may mean rewriting the project’s charter and/or scope statement. Remember, good project communication is always a critical key to successful projects.

Outsourcing Done Wrong

Some of the Worst Practices that Guarantee your Time and Money Won’t Be Well Spent An outsourcing project, especially in Information Technology (IT), can be a long and winding road studded with sweet spots and painful pitfalls. There are numerous opportunities to veer off course. At any point, companies can make irreparable errors, including forgetting proper due diligence up front, mid-project cost cutting at the expense of quality, and/or insufficient focus on knowledge transfer and training. These mistakes can ultimately cause delayed completion dates, as well as increased costs and scope creep. If you are eager to bumble your next outsourcing effort, here’s ten things to do (or Don’ts), which will put you on the fast track to failure. I’ll go into the reasons why to do the opposite of each, and we’ll see how to make the most of outsourcing without the mistakes. 1. Don’t evaluate the business case for outsourcing. Any methodology should include strategic reasons for it. In the case of outsourcing, you may be wishing to improve business focus, gain access to novel capabilities, accelerate reengineering efforts, and share or transfer risks. Before you get started with any outsourcing effort, you should look at your business reasons for it. For example, if you were buying a specific mainframe to be used for five years, you could: Estimate your up-front costs (hardware, software, and one-time costs) Estimate your new operating costs (such as maintenance) Estimate your savings (such as eliminating positions or less overhead) Estimate your increase revenue Calculate cash out (A + B) Calculate cash in (C + D) Calculate net cash flow (F – E) In this way (see Table 1.1), you can rank different projects, be they current or proposed, and get a solid picture of the best investment for your organization. 2. Don’t identify all your costs. Not identifying all the costs is the problem that pops up most often in outsourcing agreements. If you want a successful outcome, do all you can to avoid the following mistakes: Having a complex solution versus a simple one. Underestimating the project’s scope. Underestimating the costs of software and hardware (one time and recurring). Underestimating the quantity of software and hardware. Underestimating the delivery dates of software and hardware. Underestimating licensing and maintenance support coverage (one time and recurring). Not considering the inventory of new equipment and the disposal of old equipment. Forgetting about supplies and spare parts. Forgetting to supply appropriate facilities for the outsourcers. Incorrectly expecting free work from one of your main vendors. Forgetting about overtime services. Losing key resources and undertraining replacements. Having key resources working on multiple projects. Working with a long-distance outsourcer. Having no risk management plan. Having no recovery plan. If you haven’t taken a long look at what it really costs to develop a particular project in-house, as compared to outsourcing it, the supposed savings of sending work to a consultant or overseas service provider may spontaneously combust, leaving you with insufficient funds and an incomplete project. 3. Don’t worry about the big picture for deadlines. If other projects overlap your planned outsourcing project, are you prepared? Internal project schedules must be coordinated to eliminate any duplicate efforts, unknown dependent activities, out-of-sequence tasks, and payment confusions. Other potential obstacles include special promotions, the opening or closing of facilities, and moratorium dates that conflict with holidays, payroll processing, backup periods, annual disaster recovery (DR) testing, and financial closings. 4. Don’t analyze stakeholder and sponsor commitments. It happens all too often that stakeholders don’t see eye-to-eye or have different agendas, whether due to interpersonal, geographic, or cultural differences. Perhaps the project’s sponsor isn’t truly committed to the project and hinders progress by not making timely key decisions to keep it moving. Or maybe some client teams and management just don’t like conceding control to outsiders. It’s crucial to research and document all stakeholder needs and their competing obligations before you outsource the project. If you don’t, you’ll run the risk of having it torpedoed mid-course. 5. Don’t write down your conditions of satisfaction. I have worked on projects that met all the conditions of the contract (as well as being on time and within budget), and they still weren’t considered successful by the client. Why? Because the conditions of satisfaction (COS) weren’t defined or passed on to the outsourcer before the project started. A smart outsourcer knows this, and will help you develop your COS. There are usually some elements of “knowledge transfer” in the COS, and the intent of this is to ensure that intellectual property isn’t lost to the organization at the end of the contract. However, anyone who has been a part of knowledge transfer activities (see Figure 1.2); whether from the outsourcer or client perspective, will know these elements are rarely robust enough to be effective. Recognize that it’s in the outsourcer’s interest to retain knowledge in order to have ongoing revenue in the forms of support work. This is not an easy endeavor, but the client must work on developing processes and accommodating tools to effectively and efficiently collect the transferred knowledge from the outsourcer before they leave. Over and above the COS related to intelligent property, there can be other issues when dealing with local and foreign vendors. The legal system of some countries doesn’t offer intelligent property protection. This disparity allows the vendor to extract the client’s intelligent property and could result in the outsourcer to become a competitor and/or leak the knowledge to others. This has happened many times in the past with U.S. industries (i.e., computers and electronics). Intelligent property and internal technical information must be carefully controlled by the client, so there is not a loss of competitive advantage. 6. Don’t manage your relationship with the outsourcer. Most companies underestimate their own management requirements when it comes to outsourcing. What is the way around this? Have the outsourcer develop a communications plan at the start of the project to be approved by you. The plan should: Describe all stakeholders’ communication needs. Define how stakeholders will be kept informed. Identify the communication paths between project teams and stakeholders. Describe standards used for deliverables and repository information. Remember, you can’t put an outsourcing agreement in place and then walk away. Make sure that you manage the outsourcers in the same way that you would your own team. Use governance and oversight to keep an eye on what they are doing on your behalf. Track their progress regularly. If something goes wrong, it’s your project that will suffer, so keep a close eye on the work that is going on. This isn’t about micromanaging, but more about making sure that your goals are met. You wouldn’t expect to give someone else a task and hefty salary, and then never check up on them, would you? No! So, don’t do it with third parties either. All outsourcing arrangements should be based on the concept of “trust, but validate.” When working with outsourcers, you should want to build good relationships through communication, shared goals, ideas, and joint proposals. By doing this, you will obtain greater opportunities to see their workmanship and know-how in action. Another benefit of having a good relationship is that you might find the same outsourcers useful again for future projects! 7. Don’t be prepared. I have worked on outsourcing assignments in which the client wasn’t physically prepared for us (for example, no office space or facilities had been designated). This resulted in a lot of scrambling around. I have also seen clients who didn’t implement a virtual private network to support the requirements of the outsourced project. Furthermore, I have seen clients who didn’t implement the agreed-upon technology changes that were vital to fast progress on the new product. Listen to the “Boy Scouts” and make sure you have your site and your hardware ready for your consultants or an overseas offshore service provider. An element of outsourcing that very few organizations consider is the impact it can have on the client organization’s own processes. Organizations that historically conduct their own projects, or who bring individual contractors into the organization when required, can work with their own internal methodology and not be too concerned about how well aligned the approach is with anyone else. When it comes to outsourcing, that logic doesn’t apply. Not only is there a need to be able to explain the project execution approach to whomever lacks the expertise of how the client operates, but there is likely to be a need for integrating that approach with the vendor’s processes. Even more fundamental, internal processes may not exist for working with a vendor. Evaluate reviews, hand-offs, approvals, etc. 8. Don’t define your responsibilities. In my experience, the client is always quick to define the outsourcer’s responsibilities, but slow in defining their own, which includes assigning roles. This isn’t just a handoff! The degree of discipline that the client’s leadership exercises can make or break a project. To succeed, you must meet your own schedule commitments (supply appropriate equipment and people). A good tool to use is RACI Charting. This serves as an effective means of analyzing and assigning roles and responsibilities. It correlates functional roles or individuals to their level of participation in an activity by assigning codes for Responsibility, Accountability, and Communication Interfaces. This simple technique can be used any time the span of control for a process needs to be determined or developed. It is a quick means of bringing redundancies and misunderstandings to light, so that better communications can occur. Steps to complete a RACI chart include: Selecting a business process to be analyzed. Listing all of the activities associated with that process in the left-hand column of the chart. Identifying all functional roles associated with the process and listing them in the top row on the chart. Establishing participation for each activity, for all roles, by assigning codes as described below. R (Responsible) – The individual working on the activity (the doer). A (Accountable) – The individual with the yes/no authority, approval, or veto power. (Note: If two or more A’s exist, this could be a sign of problems.) C (Consult) – The individual who should be consulted prior to action; two-way communication occurs. I (Inform) – The individual who receives one-way communication and will use the information or take subsequent action. The following is a simple example of a RACI Chart that depicts what happens when a client with a computer problem outsources its in-house Help Desk to IBM. Expect the outsourcing company to outline your responsibilities in a contract or statement of work (SOW). If it doesn’t, or does a poor job in defining what it expects of you, look for a firm that knows what it’s doing. When looking at the outsourcer’s contract, look for dangerous words that should be viewed with caution. The bottom line is, are these words or descriptions really achievable? If not, there could be legal problems. For example, words ending in “ly” (fully, completely, and satisfactorily) have different interpretations in a court of law. Other dangerous words could include best efforts, best estimate, and increase, lowest, greatest, earliest, latest, optimum, minimum, and maximum. The last thing you want is to have improper or unrealistic expectations about deliverables. 9. Don’t free up internal resources to work on the new project. A parsimonious attitude toward personnel will doom your project from the start, but you can’t toss unlimited resources around either. Before the services begin, you need to designate a PM to work with the outsourcer’s PM. Your PM manages many of your responsibilities as a client, acting as a liaison between your team and the outsourcer’s project team. The PM provides data and makes decisions in a timely manner, ensures that the appropriate personnel are available to the outsourcer when needed, participates in project status meetings, helps resolve problems and escalates issues as necessary, and directs the project implementation schedule along with the outsourcer’s PM. Assigning a PM to act as the point person is not all! You may also need to deal with other personnel issues, such as hiring new people or using subcontractors to match required skills for the project, ramping up and rolling off staffing, training and learning curves, planning for holidays and vacations, and choosing personnel to commit to multiple projects. Other things that may pop up are employees resisting the different processes and methods used in your outsourcing program. This is when you especially need senior management’s commitment and support to ease the resistance. 10. Don’t select an outsourcer who understands your business. Unfortunately, many firms don’t bother spending time and energy to select the best outsourcer, and most come to regret that oversight. This is a big investment decision, and you will have time to live with it during and after the project. First, seek bids from at least two or three outsourcers. Make sure they are qualified, have references, and check out as reliable. Learn about the people the outsourcer’s uses: experience, locations, and subcontractors. Don’t assume anything when reviewing proposals. When in doubt, ask questions. Don’t base your final decision solely on the lowest bidder. And, remember to always get legal counsel before signing anything. Summary I have taken the above ten “Don’ts” and converted them into ten questions (with descriptions) for outsourcing success. There are numerous opportunities to veer off course. According to Eric Door, senior research director at the Hackett Group, an Atlanta-based strategic advisory firm, at any point, companies can make irreparable errors, including inadequate due diligence up front, cost cutting at the expense of quality, and insufficient focus on knowledge transfer and training. Use these ten questions (Table 1.3) to help ensure your success. Fill in numbers in the column labeled “Your Project,” and then add them up to get your total and see what it means. As you can see, managing outsourced projects is quite different from managing “in-house” projects. An outsourced scenario requires excellent skills, knowledge, and paying extra attention to detail. Managing outsourcing with care and forethought can build a thriving partnership and help insure future outsourcing projects will be successful. Avoid the mentioned outsourcing mistakes, and your organization will have a greater chance for success. Before I close, I wanted to point out that outsourcing projects is really about vendor management, and rarely do we ever read anything from the vendor’s point of view when looking at this process. The following are some key points a good vendor will observe and/or do. Don’t forget to evaluate the following points when choosing your next outsourcer partner: If the client-vendor relationship didn’t exist before, a Master Service Agreement (MSA) is usually drafted by the vendor to tie the knot of the new partnership. It should be followed by the statement of work (SOW). Vendors typically respond to the client’s request for proposal (RFP) by doing research, pricing their work, and presenting a proposal to the client. Good vendors usually try to keep it simple. You don’t want to work with a vendor who tries to solve too many problems or over-complicates the solution. If the vendor does a good job, the client usually comes back for a “Phase 2” to address remaining problems or take a project further. This step usually opens the door for a long-term relationship. There is always more than one way to solve a given problem, and you must be aware of this. Each approach will have pros and cons. The vendor should come with corresponding costs and savings tailored to the client’s risk desire and price-to-performance attraction. The vendor should be aware that the client’s final decision is made by human beings and not by automated systems. They should also exhibit an understanding that the client’s technology/architecture team (those assessing the vendor’s proposal) may be resistant to change. Unfortunately, this is true of most humans! If the vendor aligns its’ core strengths and values with the client’s underlying needs, they stand a better chance of winning the deal and possibly becoming a real business partner!

Power, Politics, and Providing for a Project: Part 2

Trust Building between Stakeholders and the Project Team Is a Powerful Asset In Part One of my article on power, politics, and providing for a project, we looked at two areas of importance: the project’s charter and the communications plan. I’d like to continue the conversation by outlining specific suggestions for building trust between stakeholders and project team members. Eight Tips for Building Trust Interactive communication is still the best form of communication. Be present and available to your stakeholders and team. Be a good listener by concentrating on what is being told you. Effective listening includes asking questions to clarify what is being said or asking for examples. If still in doubt, paraphrase what the speaker said to be sure that you understand what he/she meant. Using non-verbal listening techniques like making eye contact, being expressive and alert, and using body language to show emotion and agreement will increase the value of a two-way conversation. Tap into the potential of the stakeholders (and others) because they usually have value to add to the project. Practicing this is a win-win combination for you and leaves them feeling pretty good, too. For example, ask for assistance in reviewing a test plan, a memo, or an idea. When you are wrong, admit it! This can change the mood from one of confrontation to collaboration. Remember, being stubborn only builds walls (not bridges) between people. If you have bad news to deliver, don’t put it off. When you do break the news, be sensitive to your listeners and have an action plan in hand to deal with any major issues. In short, the PM needs to be an honest broker of information to be able to salvage the worst of projects. Treat others as you would like to be treated. It shows respect for the individual. Don’t be blinded by the ease of these words – there is precious treasure (or Golden Rule) here! Saying “thank you” can go a long way in gratifying people and getting their support. It’s a short, but very potent statement! Be strategic when you go to coffee or lunch. Invite a stakeholder or team member. You’ll get to know each other in an informal setting and generate a better working relationship. Communications management includes your plans for handling your project’s change requests, risks, and quality. Always remember that quality is providing a product that satisfies the customer and covers a broad area such as function, cost, minimal defects, being dependable, good level of service, being competitive and so on. Final Thoughts on Navigating Project Politics This topic has covered the importance of effective communications (especially listening) in a project. PMI states that up to 90% of a PM’s time should be spent on internal and external communications, so failure to effectively accomplish this goal will definitely have adverse effects on project performance. Many surveys have shown that ineffective communications is the number one cause of project failures. Obviously, effective communications is required between the PM, sponsor, stakeholders, and project team to help increase your chances of being successful. Another aspect of effective communications is conflict management. The important thing to remember is that conflicts can’t be left to fester and increase. A PM must be on the outlook for issues and activate a strategy to deal with them. Bring patience and respect, use a problem solving approach, and construct an agreement that works to the satisfaction of the stakeholders and other team members without creating new conflicts. As we all know change is a constant happening all the time in an evolving project. The charter is usually like the tip of an iceberg, with the other 90 percent of the project lurking underwater and unfolding over time (e.g., new people will emerge who may affect the project’s goals/approaches and chances for success). Always remember that we are all in this together – coming together is a beginning, keeping together is progress, and working together is success.

Power, Politics, and Providing for a Project: Part 1

Trust Building between Stakeholders and the Project Team Is a Powerful Asset The following statement made by Dr. Gary L. Richardson, University of Houston, is one of the most commanding I ever heard related to project management and one that all project managers (PMs) should be aware of: “Projects are natural breeding grounds for conflict resulting in ineffective human behavior, which must be dealt with effectively for the overall success and health of a project.” Every organization has unique power struggles due to changing constraints to project resources, environments, goals, and/or deliverables. Competition for resources makes conflict a dominant issue, and PMs must pay attention to company politics to be effective. Usually, the most difficult limitation for a PM is getting the right team “loaned” to them from different functional or line managers (e.g., database, security, and/or infrastructure). Keep in mind that the selected members owe their first loyalty to their functional manager, and that they might be assigned to multiple projects, which eventually might cause problems in meeting individual project milestones. Furthermore, outsourcing can come into play, often motivated by a desire to cut costs, but causing potential gaps in operating performance. I have seen many PMs assigned a full time project that runs close to a year or beyond that should have their own office and/or team work room to be more productive. More often than not, though, this isn’t allowed them, and the lack of required work space results in difficulty. Remember, organizations need to be supportive to their PMs in order to have successful projects. Trust building between stakeholders (those with a vested interest in the outcome of a project) and a project’s team fosters loyalty and results in a positive working environment that increases the chances of success. In most companies there’s room for improvement—wouldn’t you agree? Two areas, in particular, are important to look at: a project’s charter and the communications plan. We’ll cover both below. The Project Charter A new project requires planning, skilled leadership, and a little luck. Since every organization is unique, the approach or model for a formal Charter varies, but always should build a business case outlining the value of the project and procuring sign off by management. The Charter serves as a high-vision target that is used to produce a business case and hopefully leads management to further approve a more detailed definition (e.g., scope document). In other words, a Charter is like a formal press release (usually 1 – 3 pages) to the organization that a specific project is being authorized for further study of its value. At the end of the charter process, management will either decide to reject, put-on-hold, approve with modifications, or approve the development and implementation of the project. At a bare minimum, a Charter (see Figure 1.1) will include the name of the PM, project sponsor, tentative budget, and the project objectives. A project sponsor is a person who normally has a large degree of influence in the organization, typically is responsible for the budget, usually reaps the benefits of the project, and champions the project through its approval phases. Some organizations go way beyond the basic template shown in Figure 1.1 and might produce a longer charter that goes into the number of team resources needed, their names, key deliverables, realistic cost estimates, risk summary, success criteria, and what the of PM’s authority is. More detail is always better in making a “go or no go” decision, but it takes more time to do this. A long charter could end up being the foundation for a scope statement, which defines a project’s boundaries such as what is included (e.g., deliverables) and what is not included (e.g., elimination of mistakes and sometimes dangerous assumptions). A Communication Plan Project status tracking and reporting processes should be defined at the start of any project as part of the communications plan, which describes the information needs of the stakeholders, project sponsor, and the project team. This overall communications plan should cover who needs to know what, when they need to know it (e.g., weekly, bi-monthly, or monthly), and how the information should be received (e.g., paper, email, or a collaboration website). It’s important that the PM ask each stakeholder to pinpoint their preferred form and frequency of desired communication. Their needs usually depends on how active the stakeholder is in the project (e.g., an occasional contributor or someone that is providing financial/political support). There are many ways of reporting a weekly, bi-monthly, or monthly status of a project. As much as possible, Microsoft’s Project, Excel, Visio, and/or PowerPoint graphics should be used to depict the status of a project which is easier for non-technical people to visualize and understand. Depending on the size and length of a project, PMs need to have status meetings at least two to four times a month with their stakeholders to cover the progress made and mitigate risks before they become issues which could hinder the development of team relationships. Meeting less frequently allows problems to fester unchecked and could thereby do great harm to the overall project (Whitten 1995). The Useful Stakeholder Directory It’s also smart in the beginning of a new project for the PM to generate a Stakeholder Directory (see Table 1.1), which allows you to make sure you identify the right people to focus on. This is a living document that will like be in need of constant updating. If in doubt about a stakeholder, include the person, and if you find out later they aren’t interested, delete the name. It’s better to be safe than sorry. The table template below could be expanded to put in other useful fields. For example, you need to know if the stakeholder is a driver, supporter, or an observer. A driver is someone that defines the results, a supporter is someone that helps you, and an observer is someone that is interested in your activities and results. Keep in mind there might be some stakeholders who view the project negatively (e.g., a new system might reduce their head count or they have a personal agenda that is not being addressed for the good of the whole). Pay attention to these issues, left unaddressed could hurt the project’s outcome. If there are a lot of politics at play, it’s important that the PM and the sponsor recognize this and do their very best to work along with dissenting people. In Part Two of this article, I’ll be bringing some suggestions for building trust between stakeholders and project team members.

Reshaping Project Managers for the Future: Part 2

Upcoming Movements in Project Management and How You Can Prepare We started to discuss in Part 1 of this article what project management opportunities are ahead and how PMs can be getting ready for them. I pointed out that the majority of small to medium businesses (SMB) are 10 – 20 years behind the times when it comes to technology and that these companies would benefit from bringing in a project process consultant (PPC). Diagnostic Affiliates of Northeast (DAN) Let’s consider Diagnostic Affiliates of Northeast (DAN) as an example. Because of the their ailing legacy infrastructure and support systems, what pained DAN the most was the lack of in-house expertise and a growing sense of not knowing what to do as their business grew in depth and breadth. After researching a number of vendors that specialize in health systems, DAN decided to go with the popular Patient Intake Applications Suite (PIAS) from Phreesia which uses a Software as a Service (SaaS) model. This on-demand software is typically assessed by users using a thin client (a lightweight computer built to connect to a server farm from a remote location) and web browser. The choice is a common one for office systems, accounting, and customer relationship management. Phreesia (www.phreesia.com) is a healthcare software company founded in 2005 with a background of software analytics and engineering. Their future growth potential looks great! Phreesia brought in a Project Process Consultant (PPC) to study DAN’s current systems. The consultant worked with the client to decide what processes they wanted to keep, what could be configured within the modular PIAS, and what new processes would replace the legacy processes. Some of the immediate benefits of the new installed system are: Phreesia had a number of different thin client check-in devices to choose from, and DAN decided to use only the PhreeisaPad shown in mustard in Figure 1.4. This consumer-friendly tablet includes a credit card reader and allows patients to update their information, sign consent forms, and pay copays securely from their seat within the waiting room. Going a step beyond, current patients don’t have to touch the PhreeisaPad if they want to avoid picking up germs from previous patient handlers. They can go online from their own device to set up an appointment and update any information that has changed. Once logged in, users have access to additional information like left messages, medications, results, appointments, health records, etc. Simplifying arrival by decreasing paper clipboard waiting time has the benefit of freeing up administrative staff for higher valued tasks. It also leads to patients having more productive time with the medical staff. PIAS’s includes a suite of reports called “Analytics” which helps DAN to understand their intake processes and monitor performance like patient payments and operational health. Consider the value of the PPC in this case, and how he/she could be paired up with the Strategy Project Manager (more on that below) by selecting a process to pick the right projects so the organization can be successful. Business Analytics Business analytics (BA) depends on getting large amounts of high quality data across different systems (e.g., Oracle, IBM, and/or Azure databases) and deciding what subsets of data adds reporting value to the organization. This value can be used to learn “insights” from past performance, so you can do better business planning and be more competitive. Henry Ford used BA to help plan and build his assembly lines, and many companies use it today for customer loyalty programs. Another example is Microsoft’s Power BI (Business Intelligence) Desktop and their similar ecosystems (e.g., Power BI Pro), which is really a BA service where end users can create enterprise reports, live dashboards, and rich visualizations themselves versus depending on their IT department. Unless they are trained, most end users won’t have the expertise to work across different systems and will need an experienced Business Analysis Consultant (BAC) to help them accumulate the information (i.e., actionable intelligence) they need to share and run their business more effectively. This is an area all PM’s should consider in future career planning. Strategy, Strategy, Strategy Strategic Project Managers (SPMs) and Chief Project Officers (CPOs) will soon be breaking the doors down to get into the C-suite of any organization that is driven by information and technology. This person will have to know the business, be an experienced PM, be part of the portfolio decision making process, and be an effective innovator and communicator. Obviously this person has to be a skilled leader (e.g., PMO director, CIO, or COO), highly respected, and have good relationships with stakeholders! Equally important, this person would be an influential collaborator in defining and helping to deliver the organization’s strategy. The SPM or CPO serves as a crucial interface between the C-suite and the organization in translating strategy and goals into projects. He/she understands the processes and advantages that need to take place for the project to be successful. Furthermore, this person can help the organization pick the right projects. End-to-End Project Managers The previous job topics discussed in this article show where projects may transition from the PM to the business owner. End-to-end PMs go to the next level by taking ownership of a new product or service. In fact, the PM becomes responsible for providing the benefits. This is actually happening in China and slowly being embraced by Western countries. A good example of this is a Chinese company, The Alibaba Group (NYSE symbol: BABA), which is one of the world’s largest e-commerce, retail, internet, AI, and technology companies. They are fast to market being an Agile-project-based organization and quickly converting ideas into products and services. It’s a much more innovative and complete way to view PMs and project management, in general. Keep in mind these End-to-end PMs need to have good communication/salesmanship skills and be able to think strategically because they may be taking on more future projects than fit into their work domain. These types of fast-to-market organizations are looking for leaders that have less technical expertise and more end-to-end expertise with strong facilitation skills. These PMs usually develop a stronger business understanding with commercial insights, which should open the door for them moving up to the executive levels of their organizations. This type of environment could become the future direction of project management, and to get there, PMs need to get out of their comfort zones, adapt, and start playing more leadership oriented roles. It should be noted, however, that in order to go in this direction, organizations need to become more flexible overcoming silos and traditional organizational structures so the work done is project-based! Summary In the last 30 – 40 years, the growth of technology has been mind boggling! Unfortunately during this period of rapid growth, processes were left far behind. For example, many software developers are still using the methodologies (e.g., Waterfall) from post WWII (these approaches were derived from heavy manufacturers using large mainframes and don’t match up with today’s technology). Traditional projects suffer from one major problem—scope bloat or having too many features that add little or no value to a newly implemented system. Consider Microsoft Word. It may have about two hundred features in it, but how many are you actually using on a regular basis? Maybe a dozen? When a new version of Microsoft Word comes out, it will have many new features that you probably won’t be interested in or use. So, there will be no immediate rush to upgrade. The point is that technology is advancing so rapidly that it’s beginning to outpace the public’s capacity to fully understand it ramifications. This means that sometimes inventing the future can cause internal problems for some large technology companies. These companies may have to reboot their own culture and/or use project process consultants to update their delivery systems and expand product lines to have a bigger retail footprint. Project managers need to change with the times to become champions of these changes, and while they are at it, modernize project management. A focus on the areas we’ve discussed in this two part article, can help PMs future-proof themselves and differentiate from others that have a similar IQ’s and education. Overall, look at your soft skills, increase your professional networking, have a positive attitude, and be resilient. All the “reshaping” PMs need to have is the ability to help able set a strategic direction for their organization, constantly improve their communications, and learn sales skills to help build up your toolkit. As mentioned in the above, companies are beginning to realize they want to hire people that have knowledge of their business areas, as well as project management skills. This future is bright and right around the corner. Start getting ready now!

Reshaping Project Managers for the Future: Part 1

Upcoming Movements in Project Management and How You Can Prepare Have you found yourself wondering what project management opportunities are ahead and how you could be getting ready? We know most white collar jobs as they exist today are going to be radically reconfigured in the near future. Forecasting your upcoming career and getting ready for these changes will be key. Computerworld’s 2014 annual forecast survey showed that IT budgets are expected to increase with the top five priorities for spending being on the following: Security technologies Cloud computing Business analytics Application development Wireless/mobile As you can see from this list, it’s becoming more essential that every IT worker have some project management and digital-age skills, so they can thoroughly understand the underlying technology they are responsible for building. The reverse will also be true —PMs will need to have strong IT knowledge and awareness of future technologies. Reshaping roles and skills in this digital-age is needed for PMs to thrive. We know this because these technologies will continue to evolve at a faster and faster pace. I see several stages of movement that will affect the direction and roles PMs should be following. Let’s look at each individually. Agile Project Management Agile had its early origins in the mid 1990’s. True be told, initially it had very little acceptance in the IT world, but, in the past decade, the acceptance of Agile in organizations has taken off exponentially. I’d like to think this has been because of the benefits of more user transparency, the ability for frequent inspections, and the flexible adaptation capabilities! With shorter lead times and faster software development productivity (along with greater flexibility/stability), PMs need to become familiar with Agile. You don’t have to be a PM to become an Agile Scrum Master (servant-leader or project facilitator), but if you are a PM with Agile experience it’s a real plus. For an Agile project to be successful, you need a team that really works well together. Cloud computing and services are central to digital transformation. Challenges exist because existing business processes and traditional project management itself has posed a risk to successful adoption of the cloud, which many companies are moving to. Cloud projects are those that can be done in an eye blink and are not usually suited to waterfall or phased projects. Using the Agile methodology improves an organizations ability to roll out new cloud solutions and meet business needs. This rapid rollout reduces costs and increases flexibility because resources are freed up to address core business priorities and/or other projects. The whole methodology fosters a culture of innovative technological solutions and delivers better business benefits to internal and external customers. Furthermore, as a PM, you should consider the certification offered by PMI to become an Agile Certified Practitioner (PMI-ACP). Since more and more companies are starting to use Agile for projects, you would be more useful and valuable if you added this certification to your background. Agile principles and the Internet of Things (next topic) are made for each other. The pairing of these two concepts for product development projects helps to reduce the delivery life cycle time and promote the continuous and rapid flow of value. Internet of Things (IoT) The management consulting company, Mckinsey defines the Internet of Things (IoT) as follows: In what’s called IoT, sensors and actuators embedded in physical objects – from roadways to pacemakers – are linked through wired and wireless networks, often using the same Internet Protocol (IP) that connects the Internet. The sensors enable the monitoring of devices everywhere and collect a myriad of data that can be analyzed. The data is then used to understand complexities of the world, and as a result improve efficiency in all areas of life – at home and work. Examples of these “smart cities” are connected cars, smart homes, wearables (e.g., Apple watches), and different ways of measuring and analyzing big cloud data by streaming data from sensors or data-in-motion. The heart of IoT resides in the source of the data, which are the sensors. These smart devices generate data activities, happenings, and influencing dynamics that provide visibility into performance and support decision processes used by a variety of major industries (i.e., manufacturing, electric utilities, transportation, automobiles, and many retailers). OK, let’s not forget Amazon, which optimizes its operations with IoT. In short, having machines connected means you are informed to make better and faster decisions. A good example of an IoT application is SMARTank’s monitors that are designed for liquid level measurement in stationary tanks that can contain diesel, lube, home heat, propane, or gasoline. The architecture is completely wireless and the monitors “call-in” via cell phone signal several times a day. This helps with inventory planning (you know exactly when your tank levels are low and need to be replenished). The customer benefits from this by strengthening their business and mission outcomes, and it drives operational effectiveness. PMs of the future will play a major role in the implementation of IoT. Knowing the importance of accurate data and measurement, successful PMs should really become the first backers for IoT. PMs should have the skills to integrate IoT into existing systems and in setting up its handling big data. It’s important that organizations and PMs are willing to adopt new methods for using IoT to explore new business opportunities. IoT is in its early stages, but is already seen as a powerful idea—one that’s considered much bigger than its hype. IoT and other technologies (e.g., artificial intelligence or AI) are helping companies transform processes and business models, empower workforce efficiency and innovation, and personalize the customer/employee experience. All of us that use the internet are interacting with AI. For example, Amazon uses AI to guess what else we might want to buy. Don’t underestimate how much this is stimulating millions of impulse buys. According to the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), spending on IoT applications is predicted to generate $64 billion dollars by 2020 and Gartner, Inc. predicts that the IoT will be made up of 26 billion smart “units” by then. Furthermore, manufacturing, transportation and logistics, and utilities are expected to account for 50% of IoT spending by 2020. There is no question that IoT is becoming a critical part of business strategies going forward! PMs need to consider this and reshape any traditional approaches they are still hanging on to to be relevant in a changing ecosystem. A comparison between the traditional approach to project management and IoT related project management is summarized in Table 1.1 and is based on seven common factors – planning, complexity, scope, collaboration, project approach, documentation, and customer focus. Large companies like General Electric, Microsoft, IBM, and Cisco are all making major IoT contributions. According to Crunchbase, a database of start-up companies, there are almost 4,000 active IoT companies around the world. Herein lies much opportunity for PMs. For example, telecom PMs with expertise in cellular/wireless networks, utilities PMs with expertise in improving reliability, and performance PMs that have experience in using IoT sensors and data resources to identify waste delays in your logistics process will all become more and more invaluable. A Focus on Project Processes The majority of small to medium businesses (SMB) are 10 – 20 years behind the times when it comes to technology. With their outdated business systems, these companies would benefit from bringing in a project process consultant (PPC). In Part 2 we pick back up with a case study illustrating the importance of a PPC. Please tell us in the comments what you are doing to prepare for the future of Project Management.

Project Portfolio Selection Using NPV (Part 2)

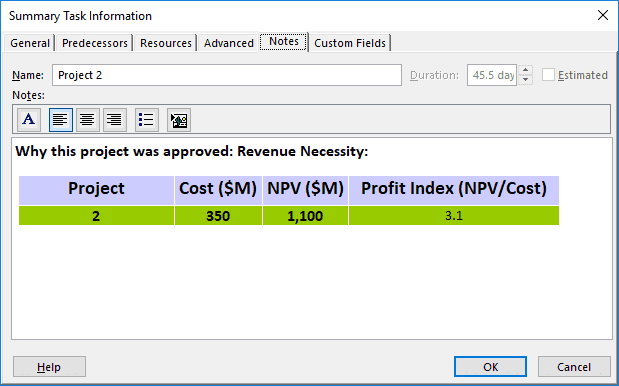

Turning the whole system into something greater than the sum of its parts In the first part of my article, we covered how the selection of projects is crucial to Project Portfolio Management (PPM), and we saw firsthand, by looking at a few case specific scenarios, how true this is. But, what about the financial formulas available in MS Excel and Project? Let’s consider how they play into this analysis. Microsoft Excel and Project Excel has many great financial formulas (i.e., =XNPV(rate,values,dates)) that are easy to use and should be used as tools for project portfolio selection. Two formulas that are related, but just “estimates” are XNPV and XIRR (or Internal Rate of Return). You must be careful when you use them, so you are not misled. As I said, they are just estimates. The main difference between the two is that XNPV calculates the value of the business today, and XIRR calculates how fast the business or rate appreciates in value (i.e. its rate of return). Microsoft Project interfaces with Excel (and Visio) offering many different kinds of visual reports showing financial information in bar graphs, pie charts, and/or line graphs. These can be very useful in project status meetings. To generate these reports in Project, go to the Report tab’s Export section and then click Visual Reports. The financial Excel reports include: baseline cost, cash flow, earned value over time, and resource cost summary. Furthermore, these reports can be customized as needed and saved as Excel files. There are three main NPV categories (Revenue, Operating, and Competitive Necessities) that you will find below in selecting what projects to work on, and these should be listed in Project’s first line (WBS = 1) under Notes. To do this, right click the first line, select Information and the Notes tab, and copy/paste the selected project’s NPV Excel data in it. I recommend doing this for historical reasons (i.e. why this individual project was selected) so that you’ll be able to provide evidence in legal proceedings, if needed. Additionally, you can later test your cost/NPV selection process to see if it’s correct or needs tweaking. See Table 1.7 below for an example. Table 1.7: Why Project 2 was Selected NPV Categories Revenue Necessity: This refers to selecting projects (from Table 1.6) that have the highest Profitability Index. Most companies want to decrease costs and increase revenues as much as they can. Operating Necessity: Sometimes an organization has to go against its formal project decision-making process because of external or internal factors. For example, Tables 1.4, 1.5, and 1.6 have the same ten projects that were prioritized and showed the best projects based on their own selection criteria. Let’s say project 10, which was not selected in Tables 1.5 and 1.6, is a new mandated U.S. federal law like the Sarbanes-Oxley Act or the Dodd-Frank Act (both related to corporate compliance on financial regulations). Of course, because of the nature of the project, this one needs to be incorporated into your operations. This means that you would use your selection criteria on the first nine projects. In a different scenario, let’s say Project 10 has been approved (another free-pass) by your board of directors and/or CEO to improve the company’s public image, which may be at a very low point. In this case, again this project would have to be implemented, which means you would use your selection criteria on the first nine projects. Other “free-pass” projects may include advoiding litigation, addressing regulatory issues, and reducing exposure. Competitive Necessity: These projects are similar to Operating Necessity projects, but are less critical. Competitive Necessity projects are usually in response to a competitor’s actions or a change in technology or markets that could lead to a new strategy for the organization. For example, computer hard drive manufacturers had to upgrade their manufacturing facilities to change from making hard disk drives (HDD) to making storage area network (SAN) drives. The long-term benefits and savings for their customers were great! The devices took up less than half the rack storage space versus using HDD, time to access data was cut in half, and the data transfer rate doubled. Likewise, if project 10 from Tables 1.5 and 1.6 is an approved competitive one, then you would use your selection criteria on the first nine projects. Other Financial Decision Considerations Payback Period: Capital budgeting refers to the period of time required for the return on the entire investment if the returns are evenly distributed over the years with little or no salvage value. Assume an investment of $500,000 is expected to produce annual returns of $100,000 for ten years. Then, the payback period for the investment to be recovered would be five years. The ratio of the investment to the annual return is 5:1. Expressed in another way, the unadjusted rate of return is 20% as follows: the $100,000 returns is divided by the $500,000 investment, which equals a 20% rate of return. As anyone should see, the math is simple to follow, but the payback period has some drawbacks. For example, it ignores cash flows after the payback period ends and ignores the time value of money. NPV does take into account the time value of money (i.e. the net cash flows at different points in time), which gives a more accurate picture of financial performance. Depreciation and Income Tax: Organizations may need to acquire capital assets that are depreciable for income tax purposes over a period of accounting periods. Assume a new host computer costs $500,000 with a life expectancy of five years with no trade-in or resale value at the end of five years. The annual tax deduction for depreciation would be $100,000 ($500,000/5) for five years. If there is a trade-in or resale value at the end of five years of $100,000, then the annual tax deduction for depreciation would be $80,000 (($500,000 – $100,000)/5). The possible tax effect of depreciation must be considered when making investments especially when depreciation deductions will reduce annual cash out-flows by paying less income tax. Reducing Risks: One of the main keys to PPM is to diversify investments in such a way as to reduce the overall risks within a portfolio. While it’s important to optimize the total financial value of projects within a portfolio, you still want to minimize the risk exposure by having early and frequent risk reviews for each project. Also, it’s important to be aware of your external risks (i.e. customers, suppliers, competitors, industry, and economy) and internal risks (i.e. resource estimations, schedule estimations, scope definitions, and scope creep). As one can see, reducing risks is part of portfolio balancing and optimization that should be done on a regular basis. It’s important to always remember some things will go wrong in pending and approved projects within an organization. Of course, it’s easier and faster to expect such issues and have a plan for how to respond. Summary Many companies still use unscientific approaches when it comes to PPM evaluation and selection. These approaches usually lead to wasted monies, resources, and unfavorable politics. Having formal methods for portfolio evaluation and selection, such as those described in this article, will go a long way for your organization and help to eliminate much of the political flavor in project selection. PPM should improve your project selection process, give you a better understanding of project value, and could help you obtain funds for a project. As much as possible, you should always want to pick projects and programs that meet your organization’s strategic goals. Be aware that many companies’ strategic plans are more like mission or vision statement than a road map, and very few companies do “post audits” that could confirm whether investments actually paid off. Even if a post audit showed negative financial outcomes, it might expose a manager’s data gathering errors and manipulation efforts. It’s important that portfolio managers have solid financial and analytical skills and understand how projects and programs can increase NPV (or other selected financial formulas) while supporting strategic goals. Furthermore, portfolio managers might consider getting certification through PMI as a Portfolio Management Professional (PfMP) to increase their skill level and/or future opportunities. There are only about 400 holders of this certification, and in my opinion, there should be more. Another PMI certification to consider, one of which there are about 2,000 holders, is the Program Management Professional (PgMP) certification. Since the PPM approach is not a “one-size fits all” solution, your organization should research other optimization methods and models for PPM evaluation and selection to find their best value equation. This could include integer linear programming that will maximize or minimize some target area, what-if-modeling, and/or software that shows inter-project dependencies to understand what is going on in other projects. All of these considerations will lead to better resource allocation. Most of these features can be found in project-portfolio software products like Microsoft Project Portfolio Management (microsoft.com) or Primavera Enterprise Project Portfolio Management (oracle.com). Some of the functionalities include staffing projects from a common resource pool and tracking activities on multiple projects to show inter-project activity dependencies. More importantly, these tools can assist in the selection of the right mix of strategic projects. Another advantage to having this kind of software is having common project communications (i.e. tracking reports and accomplishment reports). This common language fosters team collaboration throughout the organization by promoting well established project-management and data-oriented policies, processes, and procedures. The people running PPM need to learn to communicate better to build trust and to insure their messages are clear and understandable within their organization. Communication management should always include rich visual dashboards that have hyperlinks to allow people to drill down on their own time to see more detailed information. These dashboards (i.e. pie charts, Gantt charts, and status indicators) will help a PPM to deliver status information in a precise and timely manner.

Project Portfolio Selection Using NPV (Part 1)

Turning the whole system into something greater than the sum of its parts A crucial part of Project Portfolio Management (PPM) is the selection of projects. This is an ongoing dynamic process. In the following two part article, I will be demonstrating Net Present Value or NPV. PPM is simply managing your company’s resources. It has less to do with project management skills and more to do with strategic planning. In selecting projects, you want to pick the ones that create the greatest return and contribution to the strategic interests of your organization within the confines of your annual budget. Going a step beyond, you really want to optimize the portfolio and turn the whole system into something greater than the sum of its parts. Think of it this way – if each project is an instrument in your company’s orchestra, then you have programs made up of wind, percussion, and string instruments. You want someone – the conductor – to enhance the whole system by having the technical skills, leadership skills, and respectability to lead the orchestra in creating beautiful music. See Table 1.1. In many ways, PMs and musical conductors have common denominators. For example: They have the capacity and desire to lead/guide their project teams or musical ensembles. This includes cooperation and networking. They have to be good communicators. Besides verbal communication with their orchestras, conductors also communicate through hand gestures, typically with the aid of a baton, which means they need to be in good physical shape! So should PMs for that matter. They are involved in bringing talent together and scheduling activities. They have to interpret the overall project plan or musical scores. They have a rehearsal process. That is, to review work-in-process plans or practice musical scores. Practice makes perfect! They have to satisfy their customers. Whether users/stakeholders or audiences, hopefully the customers are happy people! Projects, Programs, and Portfolio Differences Throughout my career working with many users and executives, I have learned there is a lot of talk about projects and portfolios, but not much reference to programs. Many times I have been assigned a “project,” analyzed the endeavor, and realized that in actuality it was a group of three to five related projects. When I gave status updates, I always used the term “program,” although quite frequently the users and/or executives would call my endeavor a “project.” It always bothered me. What I got from this was that they really didn’t know the difference between a project and a program, or they did, they just didn’t care about the semantics (the whole “just get the darn job done!” mentality). Before I get into project portfolio selection, it’s important that we cover the differences between projects, programs, and portfolios. Portfolio managers (PfM) balance conflicting demands between programs and projects and manage them to achieve the anticipated benefits. Program management (PgM) focuses on achieving the cost, schedule, and performance objectives of the projects within the program or portfolio, while project management (PM) is largely concerned with achieving specific deliverables that support specific organizational objectives. The Standard for Portfolio Management – Third Edition (Project Management Institute, 2013c) documents the attributes, differences, and coincidences among the three (3) types of practices as follows (Table 1.2): Prioritized Project Portfolio Everyone would like to have a prioritized project portfolio that holds maximum value over a specific time period, but there are many variables (i.e. having enough money and sufficient resources with the right skills) to be considered. The key goals of the portfolio optimization process are to align project work with the strategic direction of the organization, maximize the value of the portfolio, and to balance the project portfolio. The following NPV financial case studies will hopefully provide us with the insight we need to improve a portfolio from a solid one to a much more profitable one. NPV is one of the most widely used financial attributes because it measures the financial return of an investment, which uses external factors like inflation, investment risk, and cost of borrowing money. Case 1: Maximizing NPV Let’s say the Fit-It company has a portfolio of ten new proposed projects (see Table 1.3) that require a total cost of $5 billion and could yield $11 billion for NPV. Regrettably, the company is constrained by its annual budget of $3.5 billion and needs to determine which projects to fund to maximize its potential. The first step is to rank or sort the NPV column (see Table 1.4) to find out how far we can go down the list until we run out of budget. We can afford five projects (5, 4, 10, 1, and 3) for a budget of $3.420 billion yielding a portfolio NPV of $7.150 billion. Case 2: Optimizing NPV The previously described case study is certainly feasible as far as portfolios go, but it may not be optimal. In fact, we may be able to create a better portfolio getting supreme value from the company’s annual budget of $3.5 billion. Using optimization software (developed in-house or purchased), we search for the most efficient portfolio. Optimizing software uses many variables, such as risk, budget, people, current ongoing projects, and manufacturing capacity, to arrive at the best combination of projects. Table 1.5 is an example of using optimizing software (SW). The NPV from Case 1 went from $7.150 billion to currently $7.950 billion for an increased value of $800 million. The new budget of $3.480 billion almost matches the annual budget and the number of selected projects went from five to eight. Case 3: Profitability NPV Since some executives prefer to see an annual return per project, they could look at the profitability index (i.e. Return on Investment), which is the NPV divided by the initial investment or cost to get the best combination of projects. This ratio basically gives you the biggest bang for your buck for each project. Of course, the higher the profitability index the better! I have taken the same ten proposed projects used in the previous case and ranked them by their profitability index (see Table 1.6) to get a higher NPV ($7.990 billion) than the one from the previous case described ($7.950). Also, the budget from the previous case went from $3.480 billion down to $3.450 billion, which means we saved $30 million in costs, and at the same time, increased our NPV by $40 million for a $70 million positive spread. We will pick up next time (in part 2 of my article) by considering how the financial formulas available in MS Excel and Project fit into this analysis. I will also cover several other considerations that should be made when selecting projects for portfolio management. In the meantime, what tools do you use to make project portfolio selections?